TCP/IP Won, OSI Lost. Or Did It? Clue: Both Are Horizontal

Edmund Burke said, “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” What he didn’t add, as it might have undermined his point, is that “history gets created in one moment and gets revised the next.” That’s what I like to say. And nothing could be more true when it comes to current telecom and infomedia policy and structure. How can anyone in government, academia, capital markets or the trade learn from history and make good long term decisions if they don’t have the facts straight?

I finished a book about the origins of the internet (ARPAnet, CSnet, NSFnet) called “where wizards stay up late, The Origins of The Internet” by Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon written back in 1996, before the bubble and crash of web 1.0. It’s been a major read for computer geeks and has some lessons for people interested in information industry structures and business models. I cross both boundaries and was equally fascinated by the “anti-establishment” approach by the group of scientists and business developers at BBN, the DoD and academia, as well as the haphazard and evolutionary approach to development that resulted in an ecosystem very similar to what the original founders envisioned in the 1950s.

The book has become something of a bible for internet, and those I refer to as upper layer (application), fashionistas who, unfortunately, have, and are provided in the book with, very little understanding of the middle and lower layers of the service provider “stack”. In fact the middle layers all but dissappear as far as they are concerned. While those upper layer fashionistas would like to simplify things and say, “so and so was a founder or chief contributor of the internet,” or “TCP/IP won and OSI lost,” actual history and reality suggest otherwise.

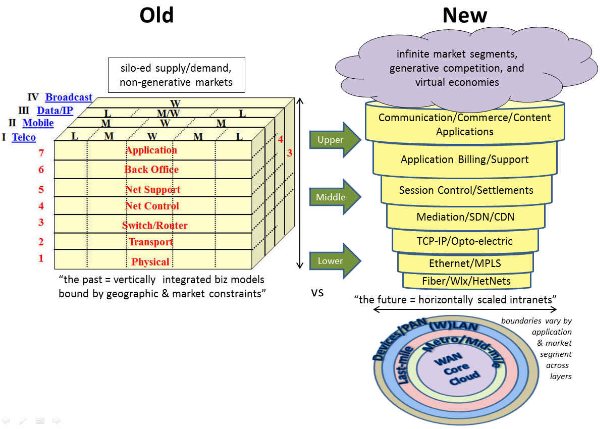

Ironically, the best way to look at the evolution of the internet is via the oft-maligned 7-layer OSI reference model. It happens to be the basis for one dimension of the InfoStack analytical engine. The InfoStack relates the horizontal layers (what we call service provisioning checklist for a complete solution) to geographic dispersion of traffic and demand on a 2nd axis, and to a 3rd axis which historically covered 4 disparate networks and business models but now maps to applications and market segments. Looking at how products, solutions and business models unfold along these axis provides a much better understanding of what really happens as 3 coordinates or vectors provides better than 90% accuracy around any given datapoint.

The book spans the time between the late 1950s and the early 1990s, but focuses principally on the late 1960s and early 1970s. Computers were enormously expensive and shared by users, but mostly on a local basis because of high cost and slow connections. No mention is made of the struggle modems and hardware vendors had to get level access to the telephone system and PCs had yet to burst on the scene. The issues around the high-cost monopoly communications network run by AT&T are only briefly mentioned; their impact and import lost to the reader.

The book makes no mention that by the 1980s development of what became the internet ecosystem really started picking up steam. After struggling to get a foothold on the “closed” MaBell system since the 1950s, smartmodems burst on the scene in 1981. Modems accompanied technology developments that had been occurring with fax machines, answering machines and touchtone phones; all generative aspects of a nascent competitive voice/telecoms markets.

Then, in 1983, AT&T was broken up and an explosion in WAN (long-distance) competition drove pricing down, and advanced intelligent networks increased the possibility of dial-around bypass. (Incidentally, by 1990s touchtone penetration in the US was over 90% vs less than 20% in the rest of the world driving not only explosive growth in 800 calling, but VPN and card calling, and last but not least the simple "touchtone" numeric pager; one of the percursors to our digital cellphone revolution). The Bells responded to this potential long-distance bypass threat by seeking regulatory relief with expanded calling areas and flat-rate calling to preserve their Class 5 switch monopoly.

All the while second line growth exploded, primarily as people connected fax machines and modems for their PCs to connect to commercial ISPs (Compuserve, Prodigy, AOL, etc...). These ISPs benefited from low WAN costs (competitive transit in layer 2), inexpensive routing (compared with voice switches) in layer 3, and low-cost channel banks and DIDs in those expanded LATAs to which people could dial up flat-rate (read "free") and remain connected all day long. The US was the only country in the world that had that type of pricing model in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Another foundation of the internet ecosystem, PCs, burst from the same lab (Xerox Parc) that was run by one of the founders of the Arpanet, Bob Taylor, who could deserve equal or more credit than Bob Kahn or Vint Cerf (inventors of TCP) for development of the internet. As well, the final two technological underpinnings that scaled the internet, Ethernet and Windows, were developed at Xerox Parc. These technology threads which should have been better developed in the book for their role in the demand for and growth of the internet from the edge.

In the end, what really laid the foundation for the internet were numerous efforts in parallel that developed outside the monopoly network and highly regulated information markets. These were all 'generative' to quote Zitrane. (And as I said a few weeks ago, they were accidental). These parallel streams evolved into an ecosystem onto which www, http, html and mosaic, were laid--the middle and upper layers--of the 1.5 way, store and foreward, database lookup “internet” in the early to mid 1990s. Ironically and paradoxically this ecosystem came together just as the Telecom Act of 1996 was being formed and passed; underscored by the fact that the term “internet” is mentioned once in the entire Act and one of the reasons I labeled the Act “farcical” back in 1996.

But the biggest error of the book in my opinion is not the omission of all these efforts in parallel with the development of TCP/IP and giving them due weight in the internet ecosystem, rather concluding with the notion that TCP/IP won and the OSI reference model lost. This was disappointing and has had a huge, negative impact on perception and policy. What the authors should have said is that a horizontally oriented, low-cost, open protocol as part of a broader similarly oriented horizontal ecosystem beat out a vertically integrated, expensive, closed and siloed solution from monopoly service providers and vendors.

With a distorted view of history it is no wonder then that:

The list of ironic and unfortunate paradoxes in policy and market outcomes goes on and on because people don’t fully understand what happened between TCP/IP and OSI and how they are inextricably linked. Until history is viewed and understood properly, we will be doomed, in the words of Burke, to repeat it. Or, as Karl Marx said, "history repeats itself twice, first as tragedy and second as farce."